The Firebird Scene 2 (1910) by Igor Stravinsky Part 2 Review About the Changes

| Fifty'Oiseau de feu The Firebird | |

|---|---|

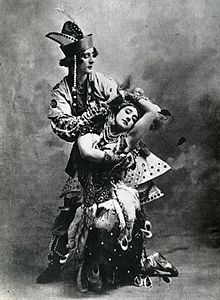

Léon Bakst: Firebird, Ballerina, 1910 | |

| Choreographer | Michel Fokine |

| Music | Igor Stravinsky |

| Based on | Russian folk tales |

| Premiere | 25 June 1910 Palais Garnier |

| Original ballet company | Ballets Russes |

| Characters | •The Firebird •Prince Ivan Tsarevich •Koschei, the Immortal •The Beautiful Tsarevna |

| Design | Aleksandr Golovin (sets) Léon Bakst (costumes) |

| Created for | Tamara Karsavina, Michel Fokine |

The Firebird (French: L'Oiseau de feu ; Russian: Жар-птица, romanized: Zhar-ptitsa ) is a ballet and orchestral concert work by the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky. Information technology was written for the 1910 Paris flavor of Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes company; the original choreography was by Michel Fokine, who collaborated with Alexandre Benois on a scenario based on the Russian fairy tales of the Firebird and the blessing and expletive it possesses for its owner. Information technology was start performed at the Opéra de Paris on 25 June 1910 and was an immediate success, catapulting Stravinsky to international fame. Although designed as a work for the stage, with specific passages accompanying characters and action, the music achieved equal if not greater recognition as a concert slice.

Stravinsky was a immature, about unknown composer when Diaghilev recruited him to create works for the Ballets Russes; L'Oiseau de feu was the first such major project. The success of the ballet was the commencement of Stravinsky's partnership with Diaghilev, which would subsequently produce further ballet productions until 1923, including the acclaimed Petrushka (1911) and The Rite of Spring (1913).

History [edit]

Stravinsky, sketched by Picasso in 1920

Background [edit]

Igor Stravinsky was the son of Fyodor Stravinsky, the chief bass at the Royal Mariinsky Theatre in St. petersburg, and Anna (née Kholodovskaya), a competent amateur vocalist and pianist from an sometime established Russian family unit. Fyodor's clan with many of the leading figures in Russian music, including Rimsky-Korsakov, Borodin and Mussorgsky, meant that Igor grew upward in an intensely musical home.[i] In 1901, Stravinsky began to report law at Saint Petersburg Imperial University, while taking private lessons in harmony and counterpoint. Sensing talent in the immature composer's early on efforts, Rimsky-Korsakov took Stravinsky under his private tutelage. Past the time of his mentor's decease in 1908, Stravinsky had produced several works, among them a Piano Sonata in F-sharp minor, a Symphony in E-flat, and a short orchestral piece titled Feu d'artifice ("Fireworks").[two] [three]

In 1909, Stravinsky'due south Scherzo fantastique and Feu d'artifice were premiered in Petrograd. Amid those in the audience was the impresario Sergei Diaghilev, who was most to debut his Ballets Russes in Paris.[iv] Diaghilev'south intention was to present new works in a distinctively 20th-century style, and he was looking for fresh compositional talent.[5] Impressed past Stravinsky, he commissioned from him orchestrations of Chopin's music for the ballet Les Sylphides.[6]

Creation [edit]

Alexandre Benois recalled that in 1908 he had suggested to Diaghilev the production of a Russian nationalist ballet,[7] an thought all the more attractive given both the newly awakened French passion for Russian dance and the expense of staging opera. The thought of mixing the mythical Firebird with the unrelated Russian tale of Koschei the Deathless perchance came from a popular child's verse by Yakov Polonsky, "A Wintertime's Journey" (Zimniy put, 1844), which includes the lines:

And in my dreams I see myself on a wolf's back

Riding along a forest path

To do battle with a sorcerer-tsar (Koschei)

In that land where a princess sits nether lock and key,

Pining backside massive walls.

There gardens environs a palace all of glass;

There Firebirds sing by night

And peck at golden fruit.[viii]

Benois collaborated with the choreographer Michel Fokine, drawing from several books of Russian fairy tales including the collection of Alexander Afanasyev, to concoct a story involving the Firebird and the evil magician Koschei. The scenery was designed past Aleksandr Golovin and the costumes by Léon Bakst.

Diaghilev commencement approached the Russian composer Anatoly Lyadov in September 1909 to write the music.[9] There is no evidence that he always accepted the commission, despite the chestnut that he was deadening to start composing the piece of work.[10] Nikolai Tcherepnin composed some music for the ballet (which he later used in his The Enchanted Kingdom), just withdrew from the projection without explanation after completing only i scene.[eleven] After deciding confronting using Alexander Glazunov and Nikolay Sokolov,[12] Diaghilev finally chose the 28-year-sometime Stravinsky, who had already begun sketching the music in anticipation of the committee.[12]

Stravinsky would later remark virtually working with Fokine that information technology meant "goose egg more than to say that we studied the libretto together, episode past episode, until I knew the exact measurements required of the music."[thirteen] Several ideas from works by Rimsky-Korsakov were used in The Firebird.[ commendation needed ] Koschei's "Infernal Trip the light fantastic" borrows the highly chromatic calibration Rimsky-Korsakov created for the character Chernobog in his opera Mlada, while the Khorovod uses the same folk melody from his Sinfonietta, Op. 31.[ citation needed ] The piano score was completed on 21 March 1910 and was fully orchestrated past May, although not earlier work was briefly interrupted by another Diaghilev commission: an orchestration of Grieg's Kobold, Op. 71, no. iii for a clemency ball dance featuring Vasily Nijinsky.[14]

Shortly thereafter, Diaghilev began to organize individual previews of The Firebird for the press. French critic Robert Brussel, who attended one of these events, wrote in 1930:

The composer, immature, slim, and uncommunicative, with vague meditative eyes, and lips set firm in an energetic looking face, was at the piano. Just the moment he began to play, the modest and dimly lit domicile glowed with a dazzling radiance. By the finish of the first scene, I was conquered: by the last, I was lost in admiration. The manuscript on the music-rest, scored over with fine pencillings, revealed a masterpiece.[15]

Reception [edit]

The Firebird was premiered by the Ballets Russes at the Palais Garnier in Paris on 25 June 1910, conducted past Gabriel Pierné.[16] Even earlier the first functioning, the visitor sensed a huge success in the making; and every performance of the ballet in that first production, as Tamara Karsavina recalled, met a "crescendo" of success.[17] "Mark him well," Diaghilev said of Stravinsky, "he is a man on the eve of celebrity."[18]

Critics praised the ballet for its integration of decor, choreography and music. "The erstwhile-gold vermiculation of the fantastic back-cloth seems to accept been invented to a formula identical with that of the shimmering web of the orchestra," wrote Henri Ghéon in Nouvelle revue française, who called the ballet "the nearly exquisite curiosity of equilibrium" and added that Stravinsky was a "delicious musician."[17] [19] Michel-Dimitri Calvocoressi hailed the young composer as the legitimate heir to The Mighty Handful.[20] The ballet's success likewise secured Stravinsky's position as Diaghilev's star composer, and there were firsthand talks of a sequel,[21] leading to the composition of Petrushka and The Rite of Spring. In Russia, nonetheless, reaction was mixed. While Stravinsky's friend Andrey Rimsky-Korsakov spoke approvingly of information technology, the press mostly took a dim view of the music, with one critic denouncing what he considered its "horrifying poverty of melodic invention."[22] A fellow Rimsky-Korsakov pupil, Jāzeps Vītols, wrote that "Stravinsky, it seems, has forgotten the concept of pleasure in sound... [His] dissonances unfortunately quickly go wearying, because at that place are no ideas hidden behind them."[23]

Sergei Bertensson recalled Sergei Rachmaninoff saying of the music: "Great God! What a work of genius this is! This is true Russia!"[24] Another colleague, Claude Debussy, who afterward became an admirer took a more sober view of the score: "What do you expect? Ane has to start somewhere."[25] Richard Strauss told the composer in private chat that he had made a "fault" in beginning the piece pianissimo instead of amazing the public with a "sudden crash." Shortly thereafter he summed up to the press his feel of hearing The Firebird for the get-go time by maxim, "it'south always interesting to hear i'south imitators."[26]

Subsequent ballet performances [edit]

The Firebird has been restaged by many choreographers, including George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins (co-choreographers), Graeme Irish potato, Alexei Ratmansky, and Yuri Possokhov.

The ballet was revived in 1934 by Colonel Wassily de Basil's visitor, the Ballets Russes de Monte-Carlo, in a production staged in London, using the original decor and costumes from Diaghilev's company.[27] The visitor after performed the ballet in Australia, during the 1936–37 tour.[28]

The piece of work was staged by George Balanchine for the New York Metropolis Ballet in 1949 with Maria Tallchief equally the Firebird, with scenery and costumes past Marc Chagall, and was kept in the repertory until 1965. The ballet was restaged by George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins in 1970 for the New York Metropolis Ballet with elaborated scenery by Chagall, and with new costumes past Karinska based on Chagall'south for the 1972 Stravinsky Festival that introduced Gelsey Kirkland as the Firebird.[29]

In 1970 Maurice Béjart staged his own version in which the ballet'due south protagonist was a young man who rose from the ranks of the revolutionists and became their leader. The lead role was danced by Michel Denard.[thirty]

The Mariinsky Ballet performed the original choreography at Covent Garden in August 2011, as role of their Fokine retrospective.[31]

The National Ballet of Canada created a version of the Firebird for idiot box, occasionally rebroadcast, in which special effects were used to get in appear that the Firebird is in flight.

On 29 March 2012, the American Ballet Theatre premiered the ballet with choreography by Alexei Ratmansky at the Segerstrom Heart for the Arts in Costa Mesa, California, starring Misty Copeland.

The Majestic Ballet staged 6 performances of the ballet at the Regal Opera Business firm in London in June 2019, with Yasmine Naghdi performing the role of the Firebird.[32] [33]

Synopsis [edit]

Drawing by Léon Bakst of Tsarevitch Ivan capturing the Firebird.

The ballet centers on the journeying of its hero, Prince Ivan. While hunting in the woods, he strays into the magical realm of the evil Koschei the Immortal, whose immortality is preserved by keeping his soul in a magic egg hidden in a catafalque. Ivan chases and captures the Firebird and is about to kill her; she begs for her life, and he spares her. As a token of thanks, she offers him an enchanted plume that he tin can use to summon her should he be in dire need.

Prince Ivan then meets thirteen princesses who are under the spell of Koschei and falls in dearest with ane of them, Tsarevna. The next day, Ivan confronts the magician and eventually they begin quarrelling. When Koschei sends his minions later on Ivan, he summons the Firebird. She intervenes, bewitching the monsters and making them trip the light fantastic an elaborate, energetic dance (the "Infernal Dance").

Wearied, the creatures and Koschei so autumn into a deep slumber. While they sleep, the Firebird directs Ivan to a tree stump where the casket with the egg containing Koschei's soul is hidden. Ivan destroys the egg, and with the spell broken and Koschei dead, the magical creatures that Koschei held captive are freed and the palace disappears. All of the "real" beings, including the princesses, awaken and with one concluding hint of the Firebird's music (though in Fokine'southward choreography she makes no appearance in that final scene on-stage), celebrate their victory.

Music [edit]

- Numbers designated past Stravinsky in the score

- Introduction

- First Tableau

- Le Jardin enchanté de Kachtcheï (The Enchanted Garden of Koschei)

- Bogeyman de l'Oiseau de feu, poursuivi par Ivan Tsarévitch (Appearance of the Firebird, Pursued past Prince Ivan)

- Danse de l'Oiseau de feu (Dance of the Firebird)

- Capture de l'Oiseau de feu par Ivan Tsarévitch (Capture of the Firebird by Prince Ivan)

- Supplications de 50'Oiseau de feu (Supplication of the Firebird) – Apparition des treize princesses enchantées (Appearance of the Thirteen Enchanted Princesses)

- Jeu des princesses avec les pommes d'or (The Princesses' Game with the Gold Apples). Scherzo

- Short apparition d'Ivan Tsarévitch (Sudden Advent of Prince Ivan)

- Khorovode (Ronde) des princesses (Khorovod (Circular Trip the light fantastic toe) of the Princesses)

- Lever du jour (Daybreak) – Ivan Tsarévitch pénètre dans le palais de Kachtcheï (Prince Ivan Penetrates Koschei's Palace)

- Carillon Féerique, bogeyman des monstres-gardiens de Kachtcheï et capture d'Ivan Tsarévitch (Magic Carillon, Appearance of Koschei'south Monster Guardians, and Capture of Prince Ivan) – Arrivée de Kachtcheï fifty'Immortel (Arrival of Koschei the Immortal) – Dialogue de Kachtcheï avec Ivan Tsarévitch (Dialogue of Koschei and Prince Ivan) – Intercession des princesses (Intercession of the Princesses) – Apparition de l'Oiseau de feu (Appearance of the Firebird)

- Danse de la suite de Kachtcheï, enchantée par l'Oiseau de feu (Dance of Koschei's Retinue, Enchanted by the Firebird)

- Danse infernale de tous les sujets de Kachtcheï (Infernal Dance of All Koschei's Subjects) – Berceuse (L'Oiseau de feu) (Lullaby) – Réveil de Kachtcheï (Koschei's Awakening) – Mort de Kachtcheï (Koschei'due south Death) – Profondes ténèbres (Profound Darkness)

- 2d Tableau

- Disparition du palais et des sortilèges de Kachtcheï, animation des chevaliers pétrifiés, allégresse générale (Disappearance of Koschei'south Palace and Magical Creations, Return to Life of the Petrified Knights, General Rejoicing)

Instrumentation [edit]

The piece of work is scored for a large orchestra with the following instrumentation:[34]

Suites [edit]

Ivan Bilibin. A warrior – costume pattern for 1931 performance of The Firebird

Besides the complete l-minute ballet score of 1909–10, Stravinsky arranged three suites for concert performance which date from 1911, 1919, and 1945.

1911 suite [edit]

- Introduction – Kashchei's Enchanted Garden – Dance of the Firebird

- Supplication of the Firebird

- The Princesses' Game with Apples

- The Princesses' Khorovod (Rondo, round dance)

- Infernal Dance of all Kashchei's Subjects[35]

Instrumentation: substantially as per the original ballet.[36] The score was printed from the same plates, with just the new endings for the movements existence newly engraved.

1919 suite [edit]

- Introduction – The Firebird and its dance – The Firebird's variation

- The Princesses' Khorovod (Rondo, round dance)

- Infernal dance of King Kashchei

- Berceuse (Lullaby)

- Finale

Instrumentation: 2 flutes (2nd too piccolo); 2 oboes (2nd also English horn for one measure); 2 clarinets; two bassoons; iv horns; two trumpets; 3 trombones; tuba; timpani; bass pulsate; cymbals; triangle; xylophone; harp; piano (also opt. celesta); strings.[37]

This suite was created in Switzerland for conductor Ernest Ansermet.[38] When it was originally published, the score contained many mistakes, which were merely stock-still in 1985.[36]

1945 suite [edit]

- Introduction – The Firebird and its dance – The Firebird's variation

- Pantomime I

- Pas de deux: Firebird and Ivan Tsarevich

- Pantomime Two

- Scherzo: Dance of the Princesses

- Pantomime III

- The Princesses' Khorovod (Rondo, round dance)

- Infernal trip the light fantastic of King Kashchei

- Berceuse (Lullaby)

- Finale

Instrumentation: two Flutes (2nd also Piccolo); 2 Oboes; 2 Clarinets; 2 Bassoons; 4 Horns; 2 Trumpets; three Trombones; Tuba; Timpani; Bass Drum; Snare Drum; Tambourine; Cymbals; Triangle; Xylophone; Harp; Piano; Strings.

In 1945, shortly earlier he caused American citizenship, Stravinsky was contacted by Leeds Music with a proposal to revise the orchestration of his beginning three ballets in guild to recopyright them in the United states of america. The composer agreed, setting aside piece of work on the finale of his Symphony in Three Movements. He proceeded to manner a new suite based on the 1919 version, adding to it and reorchestrating several minutes of the pantomimes from the original score.[39]

Get-go recordings [edit]

| Release yr | Orchestra | Conductor | Tape company | Format | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1916 | Beecham Symphony Orchestra | Sir Thomas Beecham | Columbia Graphophone Company | 78 RPM | Three excerpts from 1911 suite. First e'er commercial recording of Stravinsky's music. |

| 1924 | London Symphony Orchestra | Albert Coates | His Master's Vocalism | 78 RPM | Premiere recording of the consummate 1911 suite. |

| 1924 | Philadelphia Orchestra | Leopold Stokowski | Victor | 78 RPM | Premiere acoustic recording of the complete 1919 suite. |

| 1925 | Berlin Combo | Oskar Fried | Polydor | 78 RPM | Premiere electrical recording of the consummate 1919 suite. |

| 1947 | New York Combo-Symphony | Igor Stravinsky | Columbia Records | 78 RPM/LP | Premiere recording of the consummate 1945 suite. |

| 1960 | London Symphony Orchestra | Antal Doráti | Mercury Records | LP | Premiere recording of the complete 1911 original score. |

In pop culture [edit]

Excerpts from The Firebird were used in Bruno Bozzetto'south 1976 animated film Allegro Non Troppo [40] and in Walt Disney'due south animated film Fantasia 2000.[41]

Saviour Pirotta and Catherine Hyde's picture volume, Firebird, is based on the original stories that inspired the ballet, and was published in 2010 to gloat the ballet's centenary.[42]

The influence of The Firebird has been felt beyond classical music. Stravinsky was an of import influence on Frank Zappa, who used the melody from the Berceuse in his 1967 album Absolutely Costless, in the "Amnesia Vivace" section of the "Duke of Prunes" suite (along with a melody from The Rite of Jump).[ clarification needed ] [43] [44] Prog stone ring Aye has regularly used the ballet'southward finale as their "walk-on" music for concerts since 1971.[ commendation needed ] Jazz musician and arranger Don Sebesky featured a mash-up of the slice, with the jazz fusion composition Birds of Burn down past John McLaughlin, on his 1973 anthology Behemothic Box.[45] [46] During the 1980s and 1990s, the chord which opens the "Infernal Dance" became a widely used orchestra hit sample in music, specifically within new jack swing.[47]

It was used in the opening anniversary of Sochi 2014 during the Cauldron Lighting segment.[48]

References [edit]

- ^ Walsh 2012, §1: Background and early years, 1882–1905.

- ^ Walsh 2012, §2: Towards The Firebird, 1902–09.

- ^ Walsh 2012, §xi: Posthumous reputation and legacy: Works.

- ^ White 1961, pp. 52–53[ incomplete short commendation ]

- ^ Griffiths, Paul (2012). "Diaghilev [Dyagilev], Sergey Pavlovich". Grove Music Online. Retrieved ix August 2012. (subscription required)

- ^ Walsh 1999, p. 122.

- ^ Benois' 1910 commodity: "Ii years ago I gave vox … to the dream that a true 'Russian (or perchance Slavonic) mythology' would make its appearance in ballet"; quoted in Taruskin 1996, p. 555

- ^ Taruskin 1996, pp. 556–557.

- ^ Taruskin 1996, pp. 576–577.

- ^ Taruskin 1996, pp. 577–578.

- ^ Taruskin 1996, pp. 574–575.

- ^ a b Taruskin 1996, pp. 579.

- ^ Stravinsky, Igor; Arts and crafts, Robert (1962), Expositions and Developments. New York City: Doubleday; page 128

- ^ Walsh 1999, p. 137.

- ^ Walsh 1999, p. 138.

- ^ Walsh 2012.

- ^ a b Taruskin 1996, p. 638.

- ^ White, Eric Walter. "The Man", Stravinsky the Composer and His Works (University of California Press, 1969), p. 18.

- ^ Walsh 1999, p. 143.

- ^ Taruskin 1996, p. 639.

- ^ Taruskin 1996, p. 662.

- ^ Walsh 1999, p. 150.

- ^ Walsh 1999, p. 151.

- ^ Slonimsky 2014, p. 197.

- ^ Walsh 1999, p. 136.

- ^ Walsh 1999, p. 188.

- ^ Sorley Walker 1982, p. 41.

- ^ "Ballets Russes | What'due south On". National Library of Australia. Retrieved 5 Apr 2011.

- ^ The 1970 restaging uses only the 1945 suite equally accompaniment, as indicated by a programme note whenever the piece of work is performed.

- ^ Pitou, Spire (1990). The Paris Opera: An Encyclopedia of Operas, Ballets, Composers, and Performers; Growth and Grandeur, 1815–1914; Grand–Z. Greenwood Press. ISBN978-0-313-27783-ii.

- ^ "Mariinsky in London Roundup". The Ballet Pocketbook. 26 August 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ "The Firebird triple bill, Royal Ballet review – generous programme with Russian flavour". theartsdesk.com. 6 June 2019. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ "A gorgeous triple bill to cease The Royal Ballet's season". bachtrack.com . Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Stravinsky, I. (1910). Fifty'Oiseaux de Feu (conte dansé en 2 tableaux) [original ballet score]. Moscow: P. Jurgenson, 1911. Impress.

- ^ Johnston, Blair. "L'oiseau de feu (The Firebird), concert suite for orchestra No. one". AllMusic. Retrieved 27 Nov 2018.

- ^ a b Kramer, Jonathan D. "Stravinksy's Firebird". cincinnatisymphony.org . Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ IMSLP.

- ^ Dettmer, Roger. "50'oiseau de feu (The Firebird), concert suite for orchestra No. 2". AllMusic. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ Walsh 2006, pp. 173–175.

- ^ Chris Hicks (12 March 1991). "Allegro Non Troppo". Deseret News . Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (29 Dec 1999). "Walt'south nephew leads new Disney Fantasia". RogerEbert.com . Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ "Firebird". Catherine Hyde Home. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ^ Zappa, Frank (1989). The Real Frank Zappa book. U.s.a.: Simon & Schuster. p. 167. ISBN0-671-63870-X.

- ^ Ulrich, Charles (2018). The Big Note. Canada: New Star Books. p. 3. ISBN9781554201464.

- ^ "Giant Box – Don Sebesky | Release Info". AllMusic.

- ^ "Don Sebesky "Firebird, Bird of Fire" (from Giant Box, 1973) Mc Laughlin/Stravinsky Brew Upwardly". Archived from the original on 22 December 2021 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ "The fascinating history of the "orchestra hit" in music". kottke.org.

- ^ "The XXII Olympic Winter Games in Sochi in 2014 has opened with a thousand show thrilling spectators". Sochi Organizing Committee. 8 February 2014. Archived from the original on 8 February 2014.

Sources [edit]

- Slonimsky, Nicholas (2014). Slonimsky's Book of Musical Anecdotes. Hoboken: Taylor & Francis. ISBN978-1-135-36860-9.

- Sorley Walker, Kathrine (1982). De Basil's Ballets Russes. London: Hutchinson. ISBN0-09-147510-4. (New York, Atheneum. ISBN 0-689-11365-X)

- Taruskin, Richard (1996). Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN0-xix-816250-2.

- Walsh, Stephen (1999). Stravinsky: A Creative Spring (Russian federation and France, 1882-1934). New York Metropolis: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN0-679-41484-3.

- Walsh, Stephen (2006). Stravinsky: The 2nd Exile (France and America, 1934-1971). New York Urban center: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN0-375-40752-9.

- Walsh, Stephen (2012). "Stravinsky, Igor". Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.commodity.52818. (subscription required)

- The Firebird: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

External links [edit]

-

Media related to The Firebird at Wikimedia Eatables

Media related to The Firebird at Wikimedia Eatables

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Firebird

0 Response to "The Firebird Scene 2 (1910) by Igor Stravinsky Part 2 Review About the Changes"

Post a Comment